… What else can you do while waiting for cosmological simulations to finish other than drawing or reading? Asking for a friend.

(more…)Year: 2020

-

One Try

The idea for this essay came up during a discussion with one of my grad school referees after the 2019 season. Namely, if I so eagerly want to “save the world”, why study theoretical physics?

The following essay was the first part of my attempt to answer that question… The rest, of course, needs to be in action.

How are we sure, that Homo, our genus, is the maker of the first technical civilisation on this planet? This question persisted in my head, probably since my primary school readings of fiction and dubious mystery books.

I thought I would (as a noble form of procrastination) outline a few facts that I believe supports the case that we are the first, and, quite probably, the last, to emerge from this planet to our current level of technical (and scientific) proficiency.

Looking at our own past, some preliminary evolutionary considerations can be made. The environmental and thermodynamic conditions required for “intelligence” to be in favour was indeed rare. We owe our bipedalism, our properly placed thumbs, our sugar-craving brains, and the worlds we managed to shape with those gifts, to the K-T comet that cleared the stage for us long before our story, to the receding forests on the African highlands, to the frozen northern Pacific ocean, and to the tigers and lions that didn’t like the taste of monkey flesh too avidly … to name a few.

I have to accredit Harari’s Sapiens, for inspiring most of those above personal notions — which might be a sign to you that my thoughts on this subject have been shallow and stagnant. Take my rumblings with a grain of salt.

Still, the history of earth’s biosphere is way longer than the measly millions of years that the primates have arrived on stage. That much I do know. Time erodes a lot of things, including our trust in time itself. So, you might ask, longingly, maybe, could technology and science have happened to some entirely different branches of life than us?

Well, we know of ants that make tools and farm aphids. But probably not.

Other than the so-far general lack of archaeological footprints left by any long-gone technocratic societies, the most convincing observation, to me, is the (historic) prevalence of easily accessible natural resources.

We found, happily accepted, and sometimes wasted, the surplus of earth’s carbon cycle over tens of millions of years (…oil and coal…story for another day). But our luck did not end there. For most of our early history, we had inorganic minerals in shallow caves, if not right on the surface. And that, to me, is a hint that nobody prior has seen much use in them.

The laws of nature dictated that our societies progressed from[1] bronze to iron, i.e. against the reducing agent strength ladder. Often, after metal tools became prevalent, agriculture evolved on the massively expanding farmlands, and industry emerged with the express aim to produce increasingly complex or powerful tools. The logic might have held up to an practically exclusionary extent in our history — civilisation did not thrive at places that generally lacked minerals, even though many of those states did have excellently arable land and massive settlements.

Today, far more iron-rich and copper-rich ores come from inhospitable or technically challenging environments than when we started mining millennia ago. Among other reasons, we’ve largely dug up the ones more easily within our reach. It perhaps stands to reason, then, that if humanity is to be wiped off the surface of earth in our current era, whichever species[2] that emerges in another million years might not have any minerals to use.

They can siphon and recycle our rubbles. You think to yourself. Indeed, it might be sufficient, over geological timescales, for pulverised metropolis and dilapidated recycling plants to return some of their constituent metals to their natural state. But I doubt if this is good enough.

To begin with, without obvious hints of the way forward, in other words, without a easily accessible experience through which the future foragers can understand why these shiny bits from the ground promises a higher level of productivity, it’s possible our tech relics become more of an ornament than a industrial resource, like humans had done with various cave minerals for thousands of years ourselves. Secondly, the metals we discussed so far are far from the whole story. I will present one example of the missing pieces to try to bring my arguments together.

By this point[3], many of you might have heard of how Napoléon treated his favorite visitors with alumin(i)um cutlery, and only less important guests of his got gold plates. But today, less than 200 years later, I am typing this essay up on an Aluminum laptop keyboard, protected from some 6th-floor high wind by a presumably aluminum alloy window frame. What made this dramatic cost drop possible?

Credit human ingenuity as you please, (and I probably tend to agree), but the fundamental drive might be this naturally occurring chemical, Cryolite (Na3AlF6). It readily mixes with aluminium oxide, and it significantly lowers the melting point of the latter. This mineral was mined completely dry from the face of the earth in 1987, by the way. Only industrially prepared alternatives are available for use since[4].

The ability to synthesise cryolites is only a tiny node on human’s industrial expertise today, but once upon a time, discovering cryolites in nature, was the key for us to access the entire branch of aluminium-based technology. I cannot fathom how many little things like these played similar roles in our past, and how many achievements would have been impossible if those little factors weren’t here.

I suppose that trivia like these make me appreciate the preciousness and uniqueness of our one try at achieving cosmic greatness. The chances we took to entangle our legends with the threads of our planet, the rare finds that we stumbled upon before we knew better, and the rivers we crossed[5]. But, at the same time, the likely outcome for our story to be followed by endless stagnation and sorrow if we fail[6].

I remain optimistic, that progress in science and technology solves our existential threats, though slowly, sometimes backtracking, and not exempt from strifes and struggles. Depleted resources? We most likely can find alternatives. Dead end of knowledge, and, by extension, a lack of vision for the future? That curse is eternal.

FW, 100 seconds before midnight.

Footnotes and references

[1] Other than the obvious omissions (tin, lead), there are also gold and silver. However, as they require little to no chemical changes to be useful, I would, subjectively, count them as something no more challenging than rocks.

[2] Ant people and squid people look equally appealing to me. But again, the selection pressure on brains is a cosmically delicate thing. Boltzmann knows best.

[3] My sense of how well people around me are in knowing and using science is heavily biased as I progressed through my own education and travelled to various institutions. This is just a general comment and I will probably discuss it in full next week, when my #DailyChemistry stored on Tencent Weibo gets permanently deleted as the service shuts down. Still, I need to point out that if you’ve come for the chemical engineering… You are reading the wrong blog.

[4] Cryolite lowered the temperature required to get Aluminium via electrolysis from 2000 degrees Celsius to about 1000. From as much I can gather from my high school memory, the reaction is done in three scalable steps. You get HF by boiling Fluorites (CaF2, that glowing ore in Minecraft) in sulfuric acid. Then the HF is taken to react with an Al(OH)3 solution, after which the whole thing is heated in the presence of either NaCl or Na2CO3 to make the crystal.

[5] Hi Carl.

[6] I do not worry too much. Our ancestors have definitely taken risks like this before. On the wild grass plains, some humble animals, not the strongest, not the fastest, and without almost all ferocity, made it to become us, against a fate of extinction. Of course, my Bayesian philosophy suggest that luck might be independent between risk taking… Take good care of your nuclear button, if you have one.

-

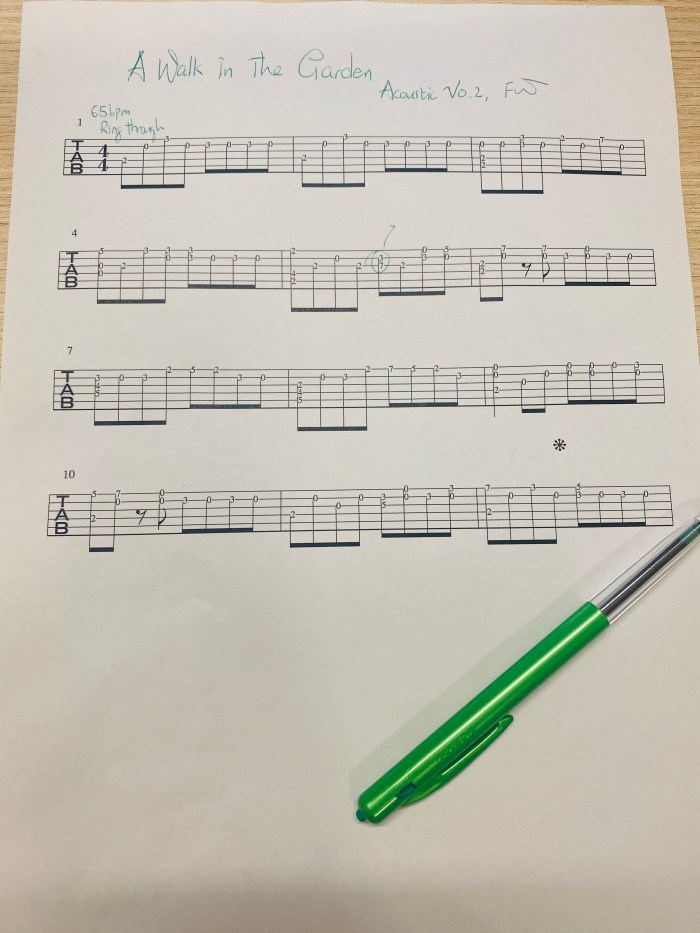

A Walk In The Garden – IrPt

Not all songs deserve a blog mention, but this one I specifically have a dream-inspired short story to follow up in late 2020.

And indeed, in that dream, I read a novella named “Little People” at a mishmash international airport, waiting to venture somewhere afar (and COVID-19-free). At least part of the story plays around my fascination with passenger aviation and people (person?) I love being “one hug away”, whatever the last phrase meant. This was how much I could jot down after waking up from that dream, anyway.

What if the purpose of life is in dreams, and we wander around in this world just to seek resources to fuel those dreams?

Meh. Unproductive idea.Also some generated tablature for the musically gifted to play with:

Tablature Generated by Logic Pro X. -

[FW AdvLab] Basic Numerical Modelling with Python

One of the latest lab manuals that I’ve developed for Auckland Physics. I find it potentially helpful for the greater audience of the internet.

This manual is intended for second-year physics majors, and assumes little prior mathematical knowledge beyond single variable calculus.

Keywords: IVP, ODE, Numerical Analysis, scipy

-

AUG

Aug is short for August, and AUG in an mRNA is a “Start” Codon, where translation first begins, or where a DNA message commonly begins to manifest as an amino acid sequence.

On the one side, the 8th month of a Gregorian year was named after Gaius Octavius Thurinus (63 BCE to 14 CE), adoptive son of Julius Caesar and the first emperor of the Roman Empire (27 BCE to 480 CE, West, and 1453 CE, East). Octavius was remembered as “Augustus”, in Latin that means sacred, venerable, or majestic (?).

His calendar system, one that pitted number prefixes (Sept-, Oct-, etc…) against actual numbers, persisted to the day of the author, and is still widely used after some patches.

On the other, A, U, and G, in molecular biology, stand for three nitrogenous bases (nucleobases), Adenine, Uracil, and Guanine. The name “Adenine” was created in 1885, rooted in “pancreas” — ἀδήν “aden”, in Greek — the organ sample from which the molecule was first identified. “Uracil” was also coined in 1885, in an attempt to synthesize derivatives of uric acid. The molecule was then found in living things (yeast cells) in 1900. Guanine was isolated in the early 1840s, as a crystal from bird excrement, which was known in Spanish as guano.

For quite some time after their discovery, some of these molecules were merely regarded as funny nitrogenous ring derivatives, and some once a vitamin (which they are not qualified to be, as the body readily synthesizes them all the time), and their logical connection wouldn’t be clearly established until the early 20th century, where the central dogma proposed a main pathway of DNA expression. In this picture, A,U, and G, molecules, when properly attached to one molecule of ribose (which makes the duos Adenosine, Uridine, and Guanosine, respectively), form codons and anticodons in RNA, which make protein expressions possible.

That I am beginning my research career in a month that sounds like “Start” is about the most trivial thing I’ve ever set to discuss around here, but it’s a coincidence 2000 years in the making, which, like most things in life, gives me that sense of weird depth and wonderful complexity. Also I suppose it is a good (minor) detail to help pinpoint myself in the stream of history.

Notes and References

The time points of the Roman Empire were taken from Encyclopedia Britannica, while the meaning of Augustus was provided by the trusty Google Latin -> English Translate.

The stories of A, U, and G Molecules are based on the following book,

Paul O. P. Ts’o. Basic Principles in Nucleic Acid Chemistry, vol. 1. (1974). pp. 7