The document is mirrored at

https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/69336

2 August, Göttingen

The document is mirrored at

https://researchspace.auckland.ac.nz/handle/2292/69336

2 August, Göttingen

The following attachment is a review presentation that I prepared as part of my application to lead the Auckland Advanced Physics Lab next year, for which I am unsuccessful.

The inability to tell beginnings and pinnacles apart is an ever-relevant phenomenon of the human condition.

References to internal and other previliged material have been removed.

There are quite a lot of ways one may get in contact with chaos should there be sufficient interest. In the broadest terms and not really wanting to be helpful, to see some chaotic motion, you can stir your coffee, play snooker on an obtuse triangular billiard table, or just go out (scratch “out” for 2021), living your life normally.

One kind of chaotic system that matters a lot to humanity, though, is the turbulent flow in gaseous media — from that measly stream propelled by the CPU cooling fan as your computer struggles to load FWPhys, to the flow lifting and occasionally shaking an airplane; from the entirety of our planet’s atmosphere, to shocks and jets in any distant nebula.

This upcoming series (Little Demo 06 A,B, and maybe even C) will be my build log of an experimental experiment to be submitted for consideration for the 2nd year physics cohort. In it, I hope to reveal some of the qualitative properties of turbulence, while introducing the able students to the modern suite of tools available to experimental fluid mechanists and researchers in related fields, assuming I can catch up myself:

This is not my PhD topic or vowed direction of research in any near future, but indeed a long-time personal curiosity since Berkeley: not frontier stuff, but a missing piece in my own training. I think I have been successful in motivating such an effort, but do need to admit the time frame may be quite stretched, even for FWPhys.

The project will be reported in three blog posts,

To conclude the intro, I guess, in terms of relevance, a properly constructed vortex visualization chamber can even be used to test the efficacy of facial masks. :p.

It began in the afternoon of Jan 20, 2021. We were cleaning the kitchen after cooking, and the sun was shining directly on me through the kitchen window. Upon feeling this, I pulled down the little window roller, and was treated to the following sight:

The narrow incoming sunbeams offered what could be described as a little slab of illumination, and when viewed from almost the opposite direction, the motion of dust particles in air could be revealed as they appear bright against a dark background. Incidentally, this reminds me of the Millikan oil drops we already have in place.

I tried recording some of the dust’s dance with my phone camera, which, through its shallow depth of field, made the dust specks more pronounced than they appear to human eye. True randomness (or perhaps not…).

For a long time, people have been building controlled observation environments that run on similar principles to my sunset coincidence. The established technique is commonly known as planar laser-induced fluorescence (PLIF).

To begin with, one prepares the light source using a laser. With some simple optics, one may manipulate the beam into the shape of a thin slice (a Laser Sheet?), and if the gas being studied contains certain molecular species that are at resonance with the laser photons, fluorescence can be produced, enabling a camera normal to the laser sheet to study a two-dimensional slice of the dynamics of the gas.

I’ve managed to find an illustration of the set up.

Annnd this is probably what I am going to build, plus some fancy computer vision code that tries to automatically analyze the footage. I will follow up on this thread as soon as time permits.

Cover image credits: Arrival (2016). (c) Paramount Pictures

(Little Demo 04 has been set to private after I realised its pointlessness without full mathematical working … it will be back online soon with additional theory.)

Their diverse shapes and forms notwithstanding, many modern plants embody self-similarity: big branches give rise to small branches, small branches give rise to leaves, and leaf stems break into primary, secondary and tertiary level veins in a similar fashion.

You might wish to point out that this self-similar pattern does not go on forever. Plants are made up of cells, after all. While their own subdivision into subatomic particles still promises a long way ahead of us, that there exists a smallest unit necessitates a definite end to the hierarchy.

On this note, if you’ve observed a leaf under a magnifying glass, you might recall the following: at cellular levels, a leaf looks like an orderly tessellation of polygons. I seem to have misplaced my own microscope a long time ago, so here’s a picture from Wikimedia to get ourselves on the same page.

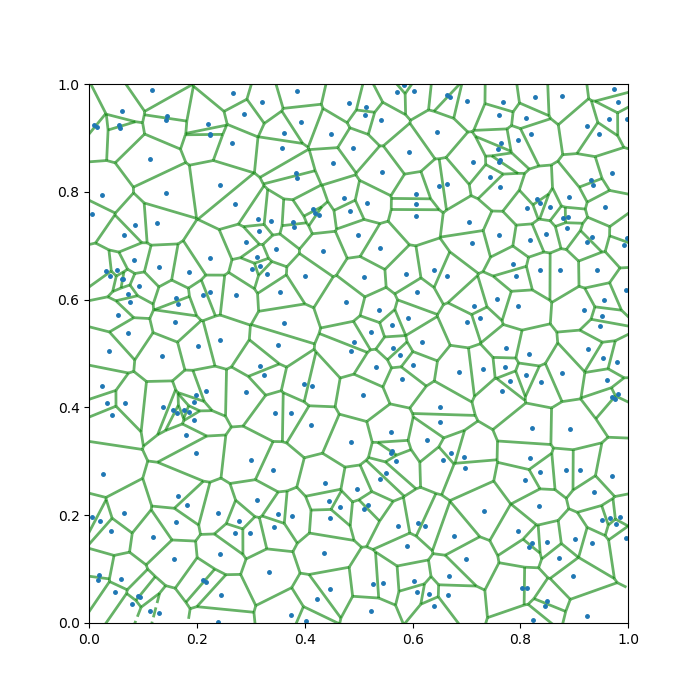

To me, the best way to describe this net-like tessellation pattern, is to state that they resemble a mathematical object known as a Voronoi diagram.

What is that? What does it have to do with leaves? And — so that this post is a demo and not exposition — can you reliably replicate this kind of pattern by hand?

The Voronoi diagram was discovered by Russian mathematician Georgy Voronoy (1868 – 1908). Some call it the Thiessen polygons, after American meteorologist Alfred Thiessen (1872 – 1956).

It has since found applications in a variety of scientific fields, such as meteorology, geoscience, condensed matter physics, and computational graphics. In recent times, people have also found them handy for things like modelling cellular signal coverage, or the spread of a pandemic.

At its core, a Voronoi diagram solves the following spacial division problem:

If I have a pancake and sprinkle on it a certain number of candies. How should you cut the pancake, such that:

In slightly more technical terms, the Voronoi diagram for a domain in ℝ2 and a set of points, divides the domain into regions according to which point is the closest.

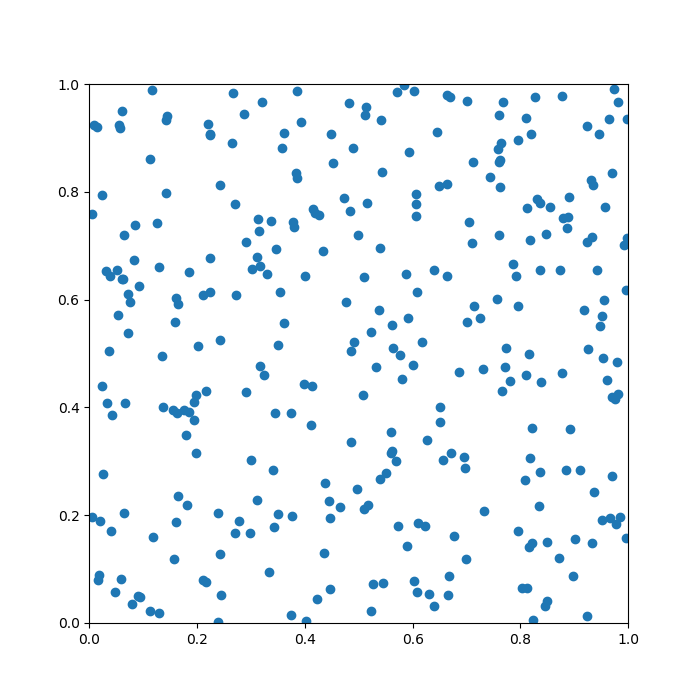

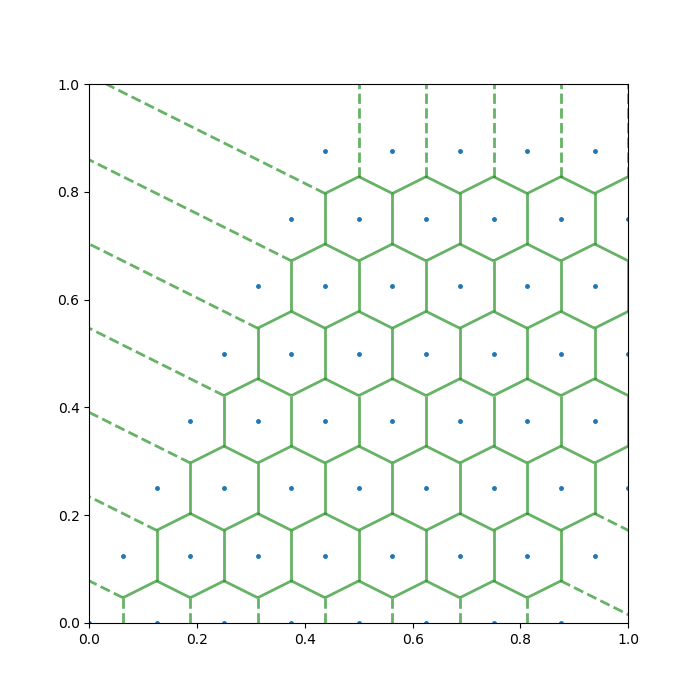

To help you understand the task, I produced a quick example below. Here, the pancake is the unit square, [0,1] × [0,1], and there are 20 points randomly sprinkled on it. The green lines are the Voronoi diagram generated from this setup.

Does it look a bit leafy already? The story is just getting started …

Tackling a general case outright may be daunting and/or confusing, so let’s start slowly. Say, we have two candies, A, and B, and wish to construct the Voronoi “single cut” for this scenario to meet our criteria above. How should we do it?

Re-interpreting the task, we want all points lying on our cut to have a equal distance to the two candies. This way and this way only, all other points falls to the correct side of the cut.

Once we’ve understood this, recollecting grade-school geometry a bit, we realise that the only cut that does job is the perpendicular bisector of the segment joining the two candies. And with this, naturally comes a method of constructing a Voronoi diagram.

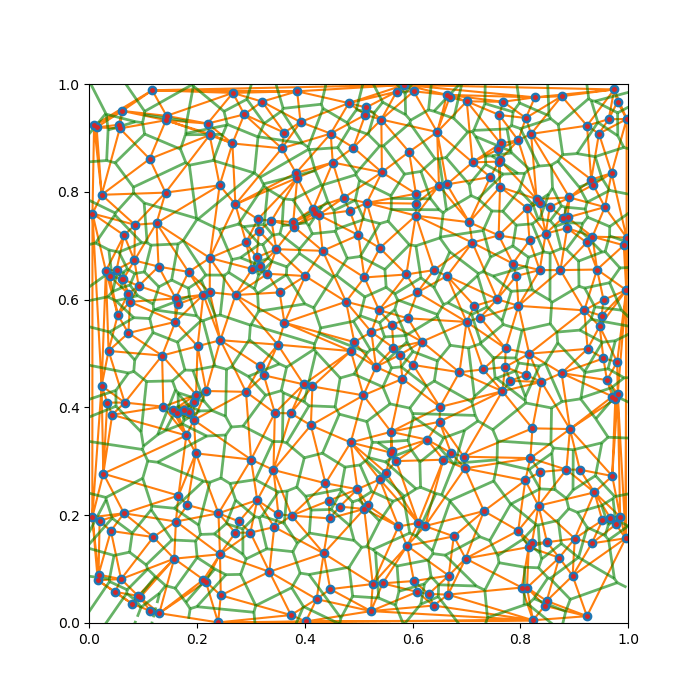

Thematically, we join all nearby candies with straight segments, and just plot the perpendicular bisectors of those segments. This guarantees that our original criteria are met locally, between any pair of nearby candies. To ensure the global satisfaction, in other words, to choose the correct pairs of candies to bisect, we need to employ the technique known as Delaunay triangulation (DT).

In 2D, DT is a way of making triangles out of a set of given points that globally maximises the smallest angle in all the product triangles. In other words, it disfavours “highly acute” triangles. This algorithm is named after another Russian mathematician, Boris Delaunay (1890 – 1980), and it is readily implemented in all modern scientific computing software (to be frank, Voronoi is too … )

Complete.

Despite how much of my childhood was spent “wanting to study plants”, I am no botanist, and this section is mainly a fascination-speculation potpourri.

To begin, for a developing leaf, the “pancake” is a region prescribed by some major leaf veins.

So, what are our candies in this context, and why Voronoi?

The eventual appearance of the leaf at our current scale of interest is partially determined by where the slowest growing group of cells is, as it — by definition — expand the slowest and creates some kind of dynamical tension on the network of the leaf veins during growth.

If we assume that the nutrients from the veins diffuse down a steady gradient within the leaf, we realise that cells farther from all its nearby veins will grow slower, and this trend will be symmetric around all veins. As such, the “candy” in this scenario corresponds to the patch of cells where the cell division / growth is the slowest.

In fact, wild Voronoi diagrams show up a lot in nature: the wing pattern of insects, a dried riverbed, and the body patterns of giraffes and sea-turtles.

Some of these probably link back to similar mechanisms as the leaf example — any 2D division problem where the speed of growth / change / colouration is linked to the distances from the “veins”, has the potential to approximately produce a Voronoi diagram.

Of course, there exists another interpretation of the Voronoi diagram. I will be amiss not to mention it.

Rather than being a logical result of constraints at the vein, we can get Voronoi if we constrain the candies instead. Say that you start to blow an (ideally elastic) ballon at each candy, and make them grow at the same rate, then the resulting boundary of these ballons will, again, be the Voronoi diagram for your initial point configuration.

As is hinted above, one can get some genuinely beautiful Voronoi diagrams if one generates Candies non-randomly.

As a start, this web designer has a page that allows you to generate Voronoi diagrams interactively for an arbitrary set of exponential spirals. A screencast of me playing with this website is shown below.

Incidentally, when you choose the golden angles (≈ 137.5 degrees) for your spiral, the Voronoi grids will approximately match the distribution of sunflower seeds, or the skin bumps on a ripe pineapple.

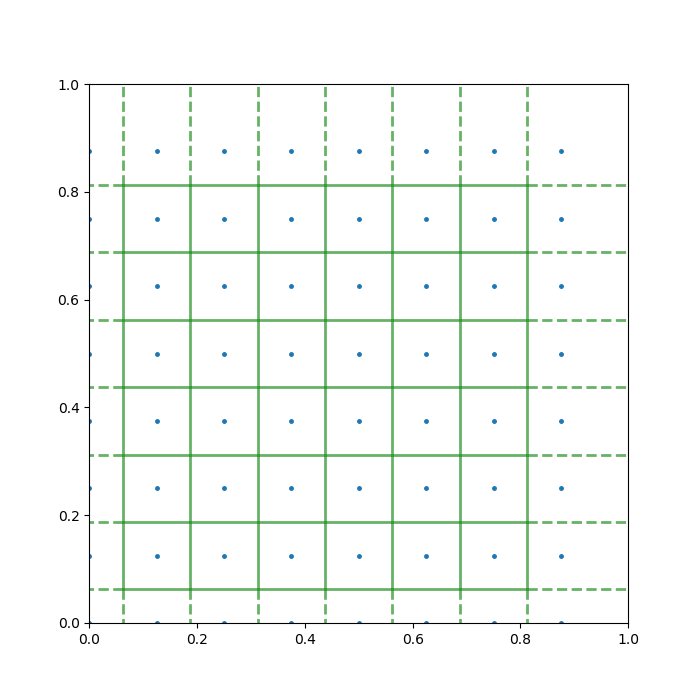

On another direction, the Voronoi grids due to 2D crystal structures can be fun too. I produced two examples below.

A mathematician should hardly be content with the Voronoi diagram as we’ve introduced around here. There are ample things left for the interested reader or aspirant researcher to generalise, and I would like to list a few:

Many modern architects look to this flavour of mathematics for inspiration, and my favourite example may be the National Aquatics Center in China, the Water Cube. All of its side walls are made up of Voronoi diagrams, while physically it also resembles a box of soap bubbles — a 3D analogue of Voronoi diagram.

This was a cancelled “Work-At-Home” experiment for physics undergraduates, due to local weather conditions, and a second thought that this project is better suited for high school students.

You may skip to the next section if you are comfortable with analytic geometry or related mathematical fields.

If you use a plane to cut the surface of an infinitely extending cone, the resulting curve of intersection is called a conic section. Depending on the relative positions of the plane and the cone, you might get an ellipse, a parabola, or a hyperbola.

On the Cartesian plane, any quadratic equation of x and y (as long as it’s not degenerate) corresponds to a conic section. That means that all conic sections follow the form:

Ax2 +Bxy+Cy2 +Dx+Ey+F =0

The earth orbits the sun with a persistent axial tilt of roughly 23.5 degrees. As a result, the latitude at which the sun directly shines overhead at solar noon (the subsolar point), oscillates between -23.5 and 23.5 degrees during the course of a year. You might have seen these photos from tropical regions, such as Hawaii, where the shadows of things disappear on certain days at noon, giving you a surreal feeling.

On this note, the long-superseded Geocentric view of the universe did leave one practical legacy: for the slow-moving creatures on the surface of the planet such as ourselves, thinking like Ptolemy of Alexandria gives us a useful framework to describe the paths that celestial bodies take during the day.

A sphere is locally flat, and so we picture the ground on which we stand as the x − y plane, with positive x- direction being east and positive y-direction being north. Readers in the Southern Hemisphere can simply flip the signs.

We then regard the rest of the universe a large sphere that surrounds us. It has two poles that are directly above the earth’s north and south poles, and the ground plane cuts into it, forming a hemispherical “sky dome”. All celestial objects, the sun included, trace almost circular paths on the dome as a result of the earth’s rotation.

This coordinate system is illustrated below.

The northern celestial pole conveniently has a bright star system nearby – Polaris – and deducing one’s latitude would be as simple as measuring the elevation angle of that star. That’s not relevant to today’s little demo, of course.

In the coordinate system defined above, we can consider a rod of unit length standing upright relative to the ground.

Assuming the earth is perfectly spherical, it is not hard to show that the tip of the rod’s shadow will move on the ground according to the following equation,

(x2 +y2 +1) sin2a=(ycosb−sinb)2

This is a family of conics (one or a pair) parametrised by two angles:

Henceforth, if we can get the curve traced by the shadow on the East-North coordinate system, we may employ nonlinear curve fit to find a and b. In other words, we can locate ourselves in space and in time (restricted to somewhere on contemporary earth …) by staring at shadows.

Of course, to see shadows change with your own eyes, you must be very bored and wait for hours. So we stare at the model instead, like happy little theorists that we are.

For most of us, notice that the a and b combinations usually describe a hyperbola, going readily to infinity to both sides, which corresponds to sunrises and sunsets. At the same time. it never hurts to remind ourselves that, when the length of the shadow is comparable to the curvature scale of the earth, our model breaks down.

For high latitudes, it’s actually possible for the tip of the shadow to trace an ellipse, which corresponds to the Midnight sun, where the sun never sets during summer. Of course, the transition case of a parabola is also possible. Question for you: Where and when does that occur?

I’ve prepared an interactive notebook (with one extra simplification model where we work out a values according to day of the year):

Demo on Desmos Graphing Calculator.

I skipped a lot of historical contexts in the interest of time, but as you may have guessed, what I described here is exactly how sundials work…

Lastly…

Take this, flatearthers!

(I was one of them until I realised some F. E. believers were actually serious… Is this a hint of the next Aperiodical blog post?)

The idea for this essay came up during a discussion with one of my grad school referees after the 2019 season. Namely, if I so eagerly want to “save the world”, why study theoretical physics?

The following essay was the first part of my attempt to answer that question… The rest, of course, needs to be in action.

How are we sure, that Homo, our genus, is the maker of the first technical civilisation on this planet? This question persisted in my head, probably since my primary school readings of fiction and dubious mystery books.

I thought I would (as a noble form of procrastination) outline a few facts that I believe supports the case that we are the first, and, quite probably, the last, to emerge from this planet to our current level of technical (and scientific) proficiency.

Looking at our own past, some preliminary evolutionary considerations can be made. The environmental and thermodynamic conditions required for “intelligence” to be in favour was indeed rare. We owe our bipedalism, our properly placed thumbs, our sugar-craving brains, and the worlds we managed to shape with those gifts, to the K-T comet that cleared the stage for us long before our story, to the receding forests on the African highlands, to the frozen northern Pacific ocean, and to the tigers and lions that didn’t like the taste of monkey flesh too avidly … to name a few.

I have to accredit Harari’s Sapiens, for inspiring most of those above personal notions — which might be a sign to you that my thoughts on this subject have been shallow and stagnant. Take my rumblings with a grain of salt.

Still, the history of earth’s biosphere is way longer than the measly millions of years that the primates have arrived on stage. That much I do know. Time erodes a lot of things, including our trust in time itself. So, you might ask, longingly, maybe, could technology and science have happened to some entirely different branches of life than us?

Well, we know of ants that make tools and farm aphids. But probably not.

Other than the so-far general lack of archaeological footprints left by any long-gone technocratic societies, the most convincing observation, to me, is the (historic) prevalence of easily accessible natural resources.

We found, happily accepted, and sometimes wasted, the surplus of earth’s carbon cycle over tens of millions of years (…oil and coal…story for another day). But our luck did not end there. For most of our early history, we had inorganic minerals in shallow caves, if not right on the surface. And that, to me, is a hint that nobody prior has seen much use in them.

The laws of nature dictated that our societies progressed from[1] bronze to iron, i.e. against the reducing agent strength ladder. Often, after metal tools became prevalent, agriculture evolved on the massively expanding farmlands, and industry emerged with the express aim to produce increasingly complex or powerful tools. The logic might have held up to an practically exclusionary extent in our history — civilisation did not thrive at places that generally lacked minerals, even though many of those states did have excellently arable land and massive settlements.

Today, far more iron-rich and copper-rich ores come from inhospitable or technically challenging environments than when we started mining millennia ago. Among other reasons, we’ve largely dug up the ones more easily within our reach. It perhaps stands to reason, then, that if humanity is to be wiped off the surface of earth in our current era, whichever species[2] that emerges in another million years might not have any minerals to use.

They can siphon and recycle our rubbles. You think to yourself. Indeed, it might be sufficient, over geological timescales, for pulverised metropolis and dilapidated recycling plants to return some of their constituent metals to their natural state. But I doubt if this is good enough.

To begin with, without obvious hints of the way forward, in other words, without a easily accessible experience through which the future foragers can understand why these shiny bits from the ground promises a higher level of productivity, it’s possible our tech relics become more of an ornament than a industrial resource, like humans had done with various cave minerals for thousands of years ourselves. Secondly, the metals we discussed so far are far from the whole story. I will present one example of the missing pieces to try to bring my arguments together.

By this point[3], many of you might have heard of how Napoléon treated his favorite visitors with alumin(i)um cutlery, and only less important guests of his got gold plates. But today, less than 200 years later, I am typing this essay up on an Aluminum laptop keyboard, protected from some 6th-floor high wind by a presumably aluminum alloy window frame. What made this dramatic cost drop possible?

Credit human ingenuity as you please, (and I probably tend to agree), but the fundamental drive might be this naturally occurring chemical, Cryolite (Na3AlF6). It readily mixes with aluminium oxide, and it significantly lowers the melting point of the latter. This mineral was mined completely dry from the face of the earth in 1987, by the way. Only industrially prepared alternatives are available for use since[4].

The ability to synthesise cryolites is only a tiny node on human’s industrial expertise today, but once upon a time, discovering cryolites in nature, was the key for us to access the entire branch of aluminium-based technology. I cannot fathom how many little things like these played similar roles in our past, and how many achievements would have been impossible if those little factors weren’t here.

I suppose that trivia like these make me appreciate the preciousness and uniqueness of our one try at achieving cosmic greatness. The chances we took to entangle our legends with the threads of our planet, the rare finds that we stumbled upon before we knew better, and the rivers we crossed[5]. But, at the same time, the likely outcome for our story to be followed by endless stagnation and sorrow if we fail[6].

I remain optimistic, that progress in science and technology solves our existential threats, though slowly, sometimes backtracking, and not exempt from strifes and struggles. Depleted resources? We most likely can find alternatives. Dead end of knowledge, and, by extension, a lack of vision for the future? That curse is eternal.

FW, 100 seconds before midnight.

[1] Other than the obvious omissions (tin, lead), there are also gold and silver. However, as they require little to no chemical changes to be useful, I would, subjectively, count them as something no more challenging than rocks.

[2] Ant people and squid people look equally appealing to me. But again, the selection pressure on brains is a cosmically delicate thing. Boltzmann knows best.

[3] My sense of how well people around me are in knowing and using science is heavily biased as I progressed through my own education and travelled to various institutions. This is just a general comment and I will probably discuss it in full next week, when my #DailyChemistry stored on Tencent Weibo gets permanently deleted as the service shuts down. Still, I need to point out that if you’ve come for the chemical engineering… You are reading the wrong blog.

[4] Cryolite lowered the temperature required to get Aluminium via electrolysis from 2000 degrees Celsius to about 1000. From as much I can gather from my high school memory, the reaction is done in three scalable steps. You get HF by boiling Fluorites (CaF2, that glowing ore in Minecraft) in sulfuric acid. Then the HF is taken to react with an Al(OH)3 solution, after which the whole thing is heated in the presence of either NaCl or Na2CO3 to make the crystal.

[5] Hi Carl.

[6] I do not worry too much. Our ancestors have definitely taken risks like this before. On the wild grass plains, some humble animals, not the strongest, not the fastest, and without almost all ferocity, made it to become us, against a fate of extinction. Of course, my Bayesian philosophy suggest that luck might be independent between risk taking… Take good care of your nuclear button, if you have one.